ArcticNet hosted its 11th Annual Scientific Meeting (ASM) from 7 to 11 December in Vancouver, British Columbia. The ASM2015 welcomed 650 researchers, students, Northerners, policy makers and stakeholders to "address the numerous environmental, social, economical and political challenges and opportunities that are emerging from climate change and modernization in the Arctic."

The EcoHealth lab collaborated in 6 poster presentations, 7 oral presentations, and 1 topical session.

Posters:

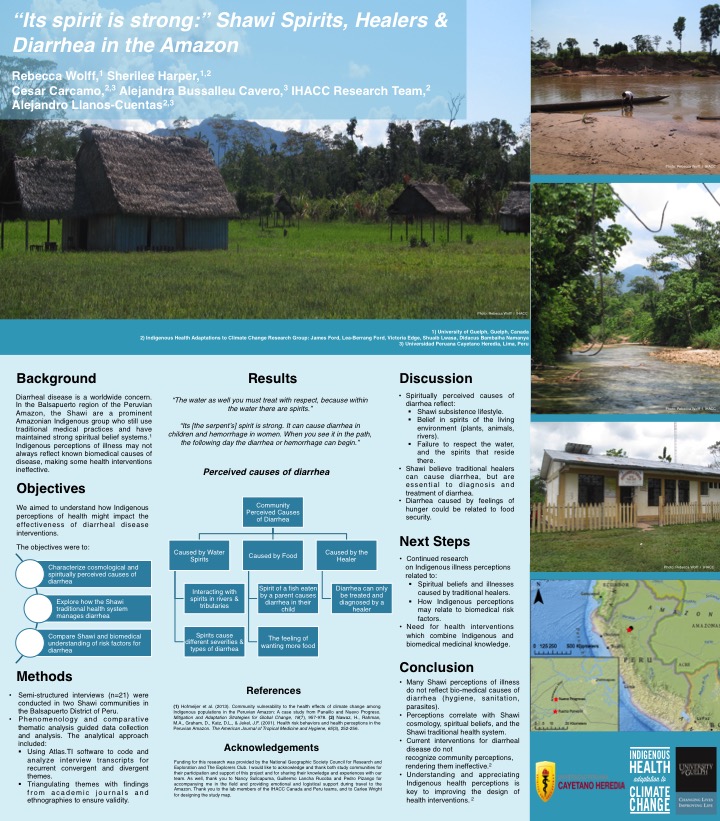

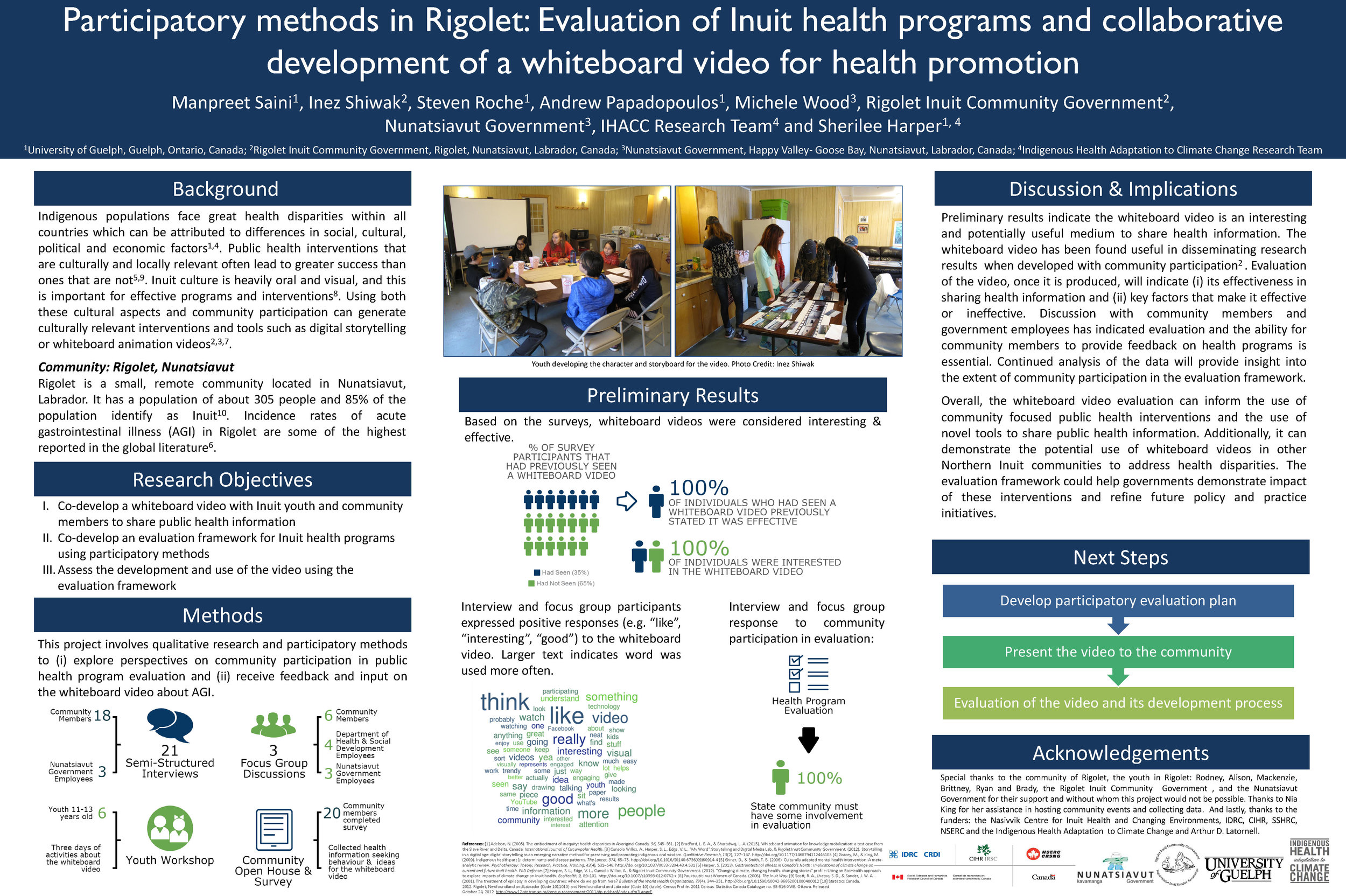

Saini M, Shiwak I, Roche S, Papadopoulos A, Wood M, Rigolet Inuit Community Government, Nunatsiavut Government, IHACC Research Team and SL Harper. December 2015. Participatory methods in Rigolet: Evaluation of Inuit health programs and collaborative development of a whiteboard video for health promotion. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting. Vancouver, Canada.

Saini M, Shiwak I, Roche S, Papadopoulos A, Wood M, Rigolet Inuit Community Government, Nunatsiavut Government, IHACC Research Team and SL Harper. December 2015. Participatory methods in Rigolet: Evaluation of Inuit health programs and collaborative development of a whiteboard video for health promotion. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting. Vancouver, Canada.

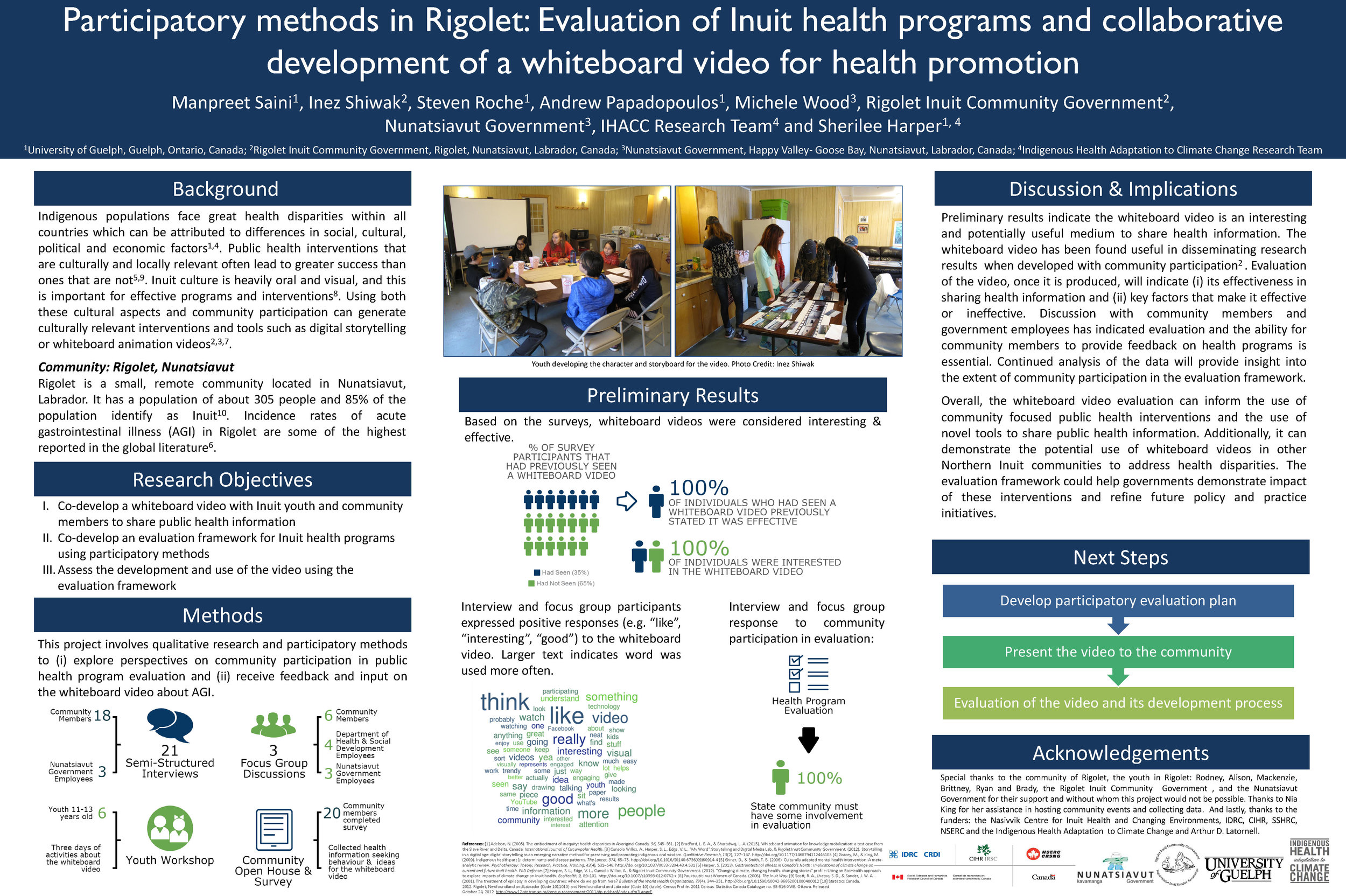

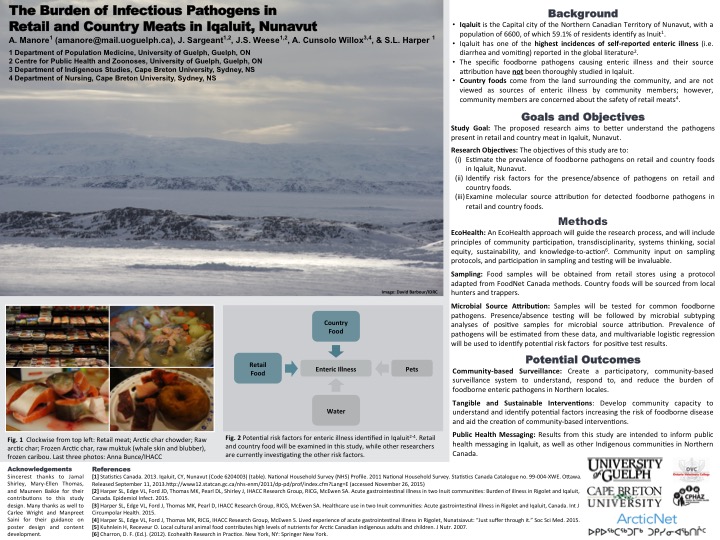

Manore A, Sargeant J, Weese JS, Cunsolo Willox A and Harper SL. December 2015. The burden of infectious pathogens in retail and country meats in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting. Vancouver, Canada.

Manore A, Sargeant J, Weese JS, Cunsolo Willox A and Harper SL. December 2015. The burden of infectious pathogens in retail and country meats in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting. Vancouver, Canada.

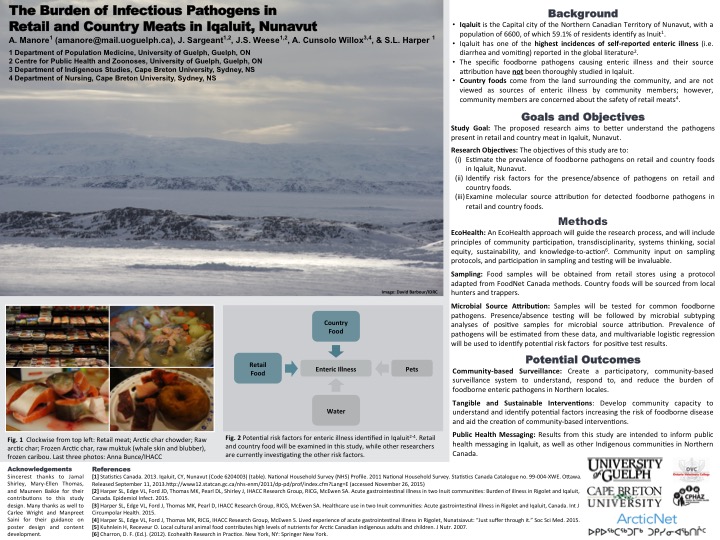

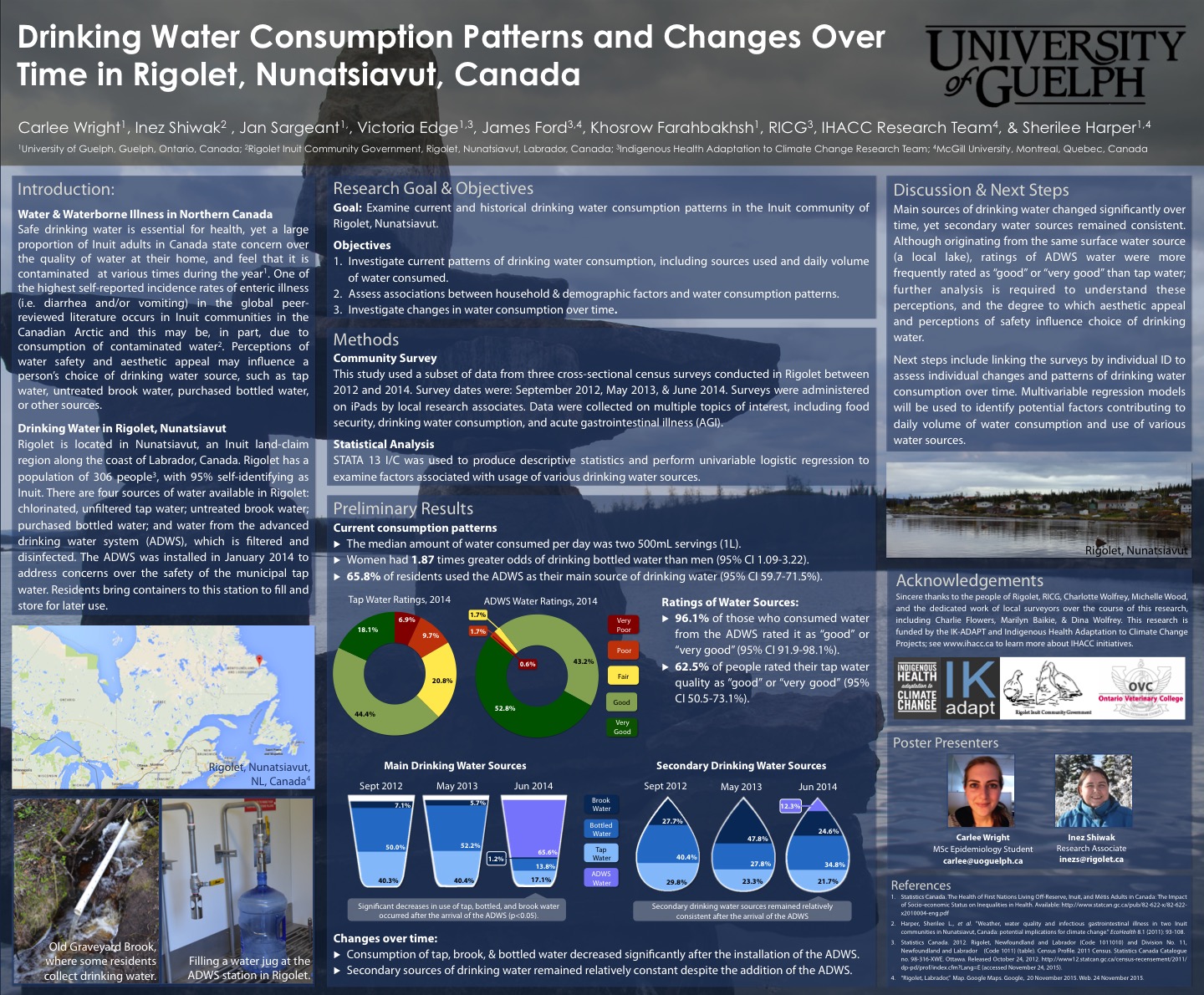

Wright C, Shiwak I, Sargeant J, Edge V, Ford J, Farahbakhsh K, Rigolet Inuit Community Government, Nunatsiavut Government, IHACC Research Team and SL Harper. December 2015. Drinking water consumption patterns and changes over time in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

Wright C, Shiwak I, Sargeant J, Edge V, Ford J, Farahbakhsh K, Rigolet Inuit Community Government, Nunatsiavut Government, IHACC Research Team and SL Harper. December 2015. Drinking water consumption patterns and changes over time in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

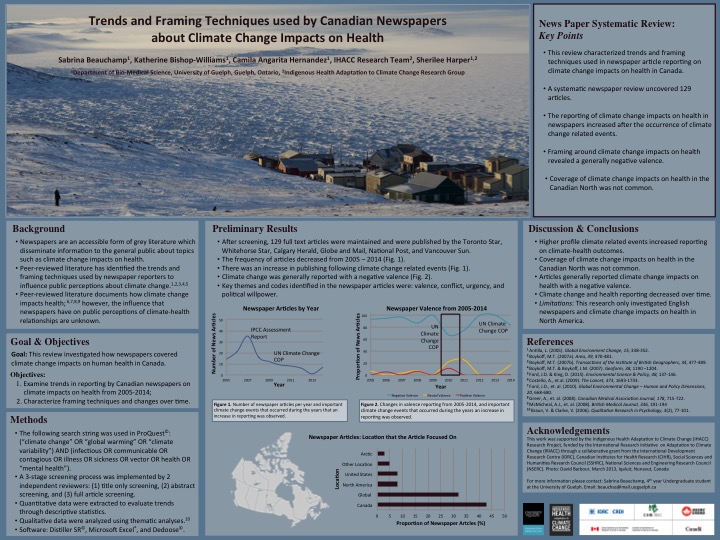

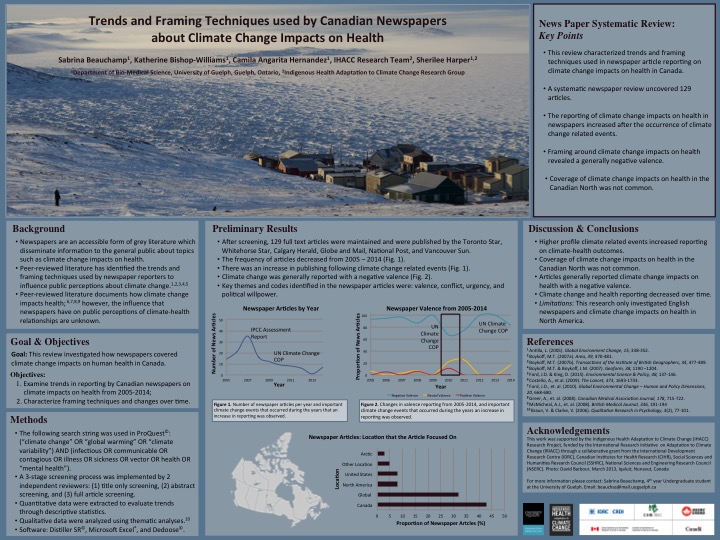

Beauchamp SL, Bishop-Williams KE, Hernandez CA, IHACC Research Team and SL Harper. December 2015. Trends and framing techniques used by Canadian newspapers about climate change impacts on health. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

Beauchamp SL, Bishop-Williams KE, Hernandez CA, IHACC Research Team and SL Harper. December 2015. Trends and framing techniques used by Canadian newspapers about climate change impacts on health. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

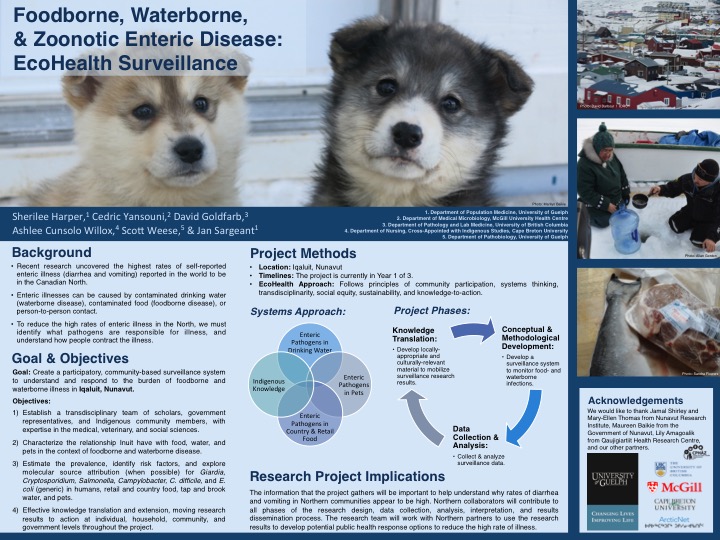

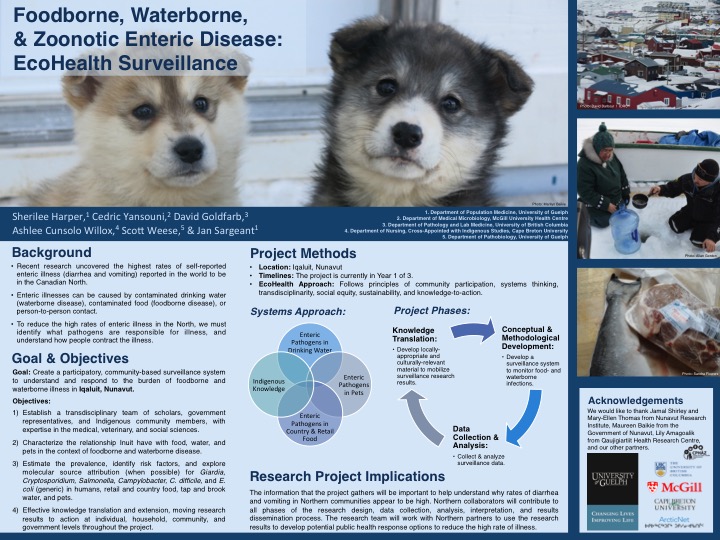

Harper SL, Yansouni C, Goldfarb D, Cunsolo Willox A, Weese S, and J Sargeant. December 2015. Foodborne, waterborne, and zoonotic enteric disease: EcoHealth surveillance for environmental health. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

Harper SL, Yansouni C, Goldfarb D, Cunsolo Willox A, Weese S, and J Sargeant. December 2015. Foodborne, waterborne, and zoonotic enteric disease: EcoHealth surveillance for environmental health. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

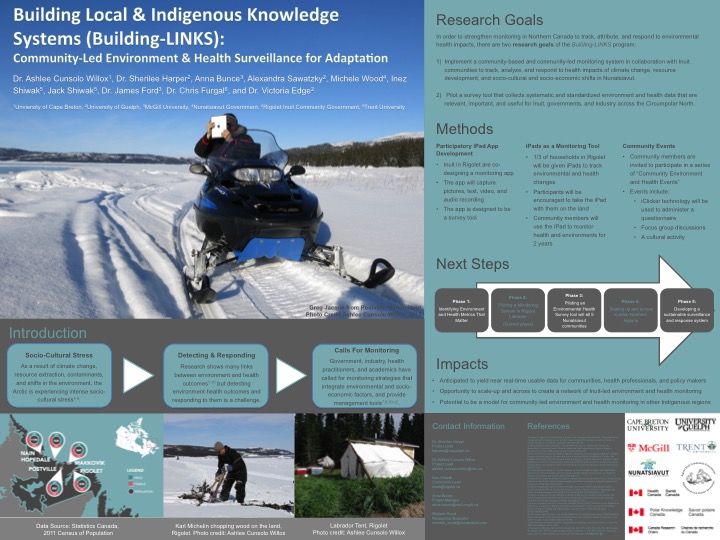

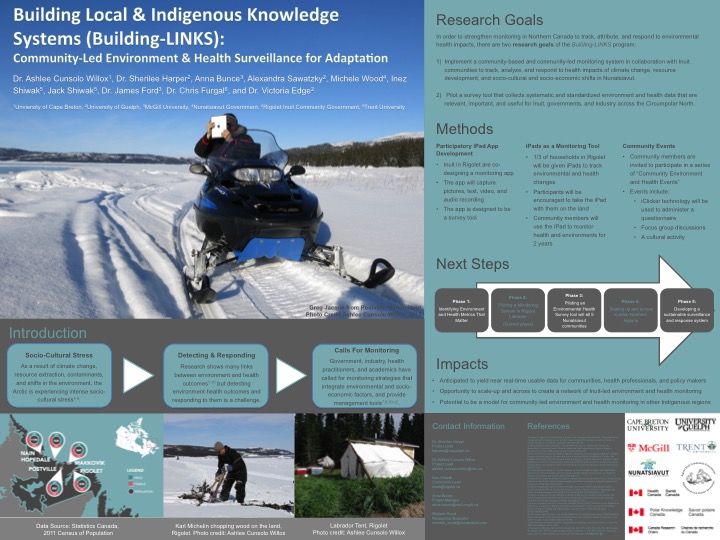

Cunsolo Willox A, Harper SL, Bunce A, Gillis D, Sawatzky A, Shiwak I, Shiwak J, Ford J, Furgal C, and VL Edge. Building Local & Indigenous Knowledge Systems (Building LINKS): Community-led environment & health surveillance for adaptation. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

Cunsolo Willox A, Harper SL, Bunce A, Gillis D, Sawatzky A, Shiwak I, Shiwak J, Ford J, Furgal C, and VL Edge. Building Local & Indigenous Knowledge Systems (Building LINKS): Community-led environment & health surveillance for adaptation. Poster Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

https://twitter.com/TWPFS/status/674629835348553728

Oral Presentations:

Saini M, Shiwak I, Roche S, Papadopoulos A, Wood M, Rigolet Inuit Community Government, Nunatsiavut Government, IHACC Research Team and SL Harper. December 10, 2015. Participatory methods in Rigolet: Evaluation of Inuit health programs and collaborative development of a whiteboard video for health promotion. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting. Vancouver, Canada.

Wright C, Shiwak I, Sargeant J, Edge V, Ford J, Farahbakhsh K, Rigolet Inuit Community Government, Nunatsiavut Government, IHACC Research Team and SL Harper. December 10, 2015. Drinking water consumption patterns and changes over time in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut. Oral Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

Harper SL, Yansouni C, Goldfarb D, Cunsolo Willox A, Weese S, and J Sargeant. December 11, 2015. Foodborne, waterborne, and zoonotic enteric disease: EcoHealth surveillance for environmental health. Oral Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

Desai S, Muchaal P, Pernica J, Smeija M, Harper SL, Miners A, Baikie M, and D. Goldfarb. December 22, 2015. Molecular microbiology of acute gastroenteritis in children under 5 years of age in Nunavut, Canada in 2014/15. Oral Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

Goldfarb DM, Miners A, Baikie M, Harper SL, and C. Yansouni. December 11, 2015. Building a research agenda for Arctic enteric infections research. Oral Presentation. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

Soucie TA, Arreak T, Harper SL, Jamieson R, Hansen LT, Jolicoeur L, Shirley J, L’Hérault V, and the Elders of Mittimatalik. December 8, 2015. Building capacity to monitor the risk of climate change on water quality on human health: A two year journey expanding community-based leadership in Pond Inlet. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

Yansouni CP, Harper SL, and D. Goldfarb. December 11, 2015. Understanding the epidemiology, microbiology, and growth trajectories of children with enteric infections in Nunavik and Nunavut: A prospective cohort study. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting, Vancouver, Canada.

https://twitter.com/Sherilee_H/status/675079115473596419

https://twitter.com/Sherilee_H/status/675102636794896387

https://twitter.com/Sherilee_H/status/675099438520655872

Topical Sessions:

Harper SL, Goldfarb D, and C Yansouni. December 11, 2015. The Scoop on Northern Poop: Foodborne, Waterborne, and Zoonotic Infections in the Canadian North. 11th ArcticNet Annual Scientific Meeting. Vancouver, Canada.

https://twitter.com/Sherilee_H/status/674595694867451904

https://twitter.com/jamiesno/status/673607031669039104