Sherman, M., Berrang‐Ford, L., Lwasa, S., Ford, J., Namanya, D.B., Llanos‐Cuentas, A., Maillet, M., Harper, S.L., IHACC Research Team. (2016). Drawing the line between adaptation and development: a systematic literature review of planned adaptation in developing countries. WIREs Clim Change2016. doi: 10.1002/wcc.416. Click here for free access to the article (open access). Abstract: Climate change adaptation is increasingly considered an urgent priority for policy action. Billions of dollars have been pledged for adaptation finance, with many donor agencies requiring that adaptation is distinct from baseline development. However, practitioners and academics continue to question what adaptation looks like on the ground, especially in a developing country. This study examines the cur- rent framing of planned adaptation amidst low socioeconomic development and considers the practical implications of this framing for adaptation planning. Three overarching approaches to planned adaptation in a developing country context emerged in a systematic review of 30 peer-reviewed articles published between 2010 and 2015, including: (1) technocratic risk management, which treats adaptation as additional to development, (2) pro-poor vulnerability reduction, which acknowledges the ability of conventional development to foster and act as adaptation, and (3) sustainable adaptation, which suggests that adaptation should only be integrated into a type of development that is socially and environmentally sustainable. Over half of ‘sustainable adaptation’ articles in this review took a critical adaptation approach, drawing primarily from political ecology and post-development studies, and emphasizing the malleability of adaptation. The reviewed articles highlight how the different framings of the relationship between adaptation and development result in diverse and sometimes contradictory messages regarding adaptation design, implementation, funding, monitoring, and evaluation. This review illustrates the need to continually interrogate the multiple framings of adaptation and development and to foster a pragmatic and pluralistic dialogue regarding planned adaptation and transformative change in developing countries.

New Publication! Vulnerability and adaptive capacity of Inuit women to climate change

Congratulations to Anna Bunce on her recent publication in Natural Hazards, entitled Vulnerability and adaptive capacity of Inuit women to climate change: a case study from Iqaluit, Nunavut.

While human dimensions of climate change research in the Arctic primarily focuses on men, Anna worked closely with a group of women to understand how climate change impacted them.

Congratulations to Anna Bunce on her recent publication in Natural Hazards, entitled Vulnerability and adaptive capacity of Inuit women to climate change: a case study from Iqaluit, Nunavut.

While human dimensions of climate change research in the Arctic primarily focuses on men, Anna worked closely with a group of women to understand how climate change impacted them.

Citation: Bunce, A., Ford, J., Harper, S.L., Edge, V., and IHACC Research Team. (2016). Vulnerability and adaptive capacity of Inuit women to climate change: a case study from Iqaluit, Nunavut. Nat Hazards. DOI 10.1007/s11069-016-2398-6

ABSTRACT: Climate change impacts in the Arctic will be differentiated by gender, yet few empirical studies have investigated how. We use a case study from the Inuit community of Iqaluit, Nunavut, to identify and characterize vulnerability and adaptive capacity of Inuit women to changing climatic conditions. Interviews were conducted with 42 Inuit women and were complimented with focus group discussions and participant observation to examine how women have experienced and responded to changes in climate already observed. Three key traditional activities were identified as being exposed and sensitive to changing conditions: berry picking, sewing, and the amount of time spent on the land. Several coping mechanisms were described to help women manage these exposure sensitivities, such as altering the timing and location of berry picking, and importing seal skins for sewing. The adaptive capacity to employ these mechanisms differed among participants; however, mental health, physical health, traditional/western education, access to country food and store bought foods, access to financial resources, social networks, and connection to Inuit identity emerged as key components of Inuit women’s adaptive capacity. The study finds that gender roles result in different pathways through which changing climatic conditions affect people locally, although the broad determinants of vulnerability and adaptive capacity for women are consistent with those identified for men in the scholarship more broadly.

On Parliament Hill to talk about why research matters!

Written by Alexandra Sawatzky, PhD Student On May 18th, Sheri and I travelled to Ottawa to take part in the “Research Matters Pop-Up Research Park” at Parliament Hill. We were both honoured and humbled to represent the University of Guelph at this gathering.

Shortly after our arrival at Parliament, we headed upstairs to attend Question Period in the House of Commons. Having the chance to experience this snapshot of political life firsthand was incredible, an added bonus to our already stimulating day.

Following Question Period, we made our way down the hall to set up for the Pop-Up Research Park. The Research Park served as an opportunity for us, alongside other Ontario university researchers, students, and industry or community partners, to engage with MPs and other senior government officials to discuss and share our research.

Each pair or group of researchers was asked to stand under a banner displaying a photo that described our work, as well as a catalytic question that was meant to ignite conversation. While there was an incredible diversity of research topics around the room, all topics related to issues impacting Canadians where they live and work. Sheri and I were there to speak about our experiences working alongside the Inuit community of Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Labrador to develop a participatory environment-health surveillance program. As our work is premised on creating and maintaining strong relationships with this community, we posed the question: Can community-university collaboration enhance Inuit health and wellbeing?

We connected with MPs from across the country, including Yvonne Jones, MP for Labrador. Sheri also had the honour of meeting Dr. Jane Philpott, Minister of Health. Although we were mainly discussing ideas and themes specific to our research, these ideas and themes – such as the theme of collaboration – resonated with everyone we spoke with. Indeed, we also engaged in discussions about the overarching reason that brought us all together in the first place – the importance of strengthening partnerships and communication between research, government, industry, and communities.

Strong partnerships and effective communication are needed in order to support innovation, collaboration, and better futures for all sectors of society. Research-based innovation would not be possible without the partnerships between industry, academia, and government –partnerships that are created and reinforced through events such as this Research Park.

Participating in this event demonstrated to us how important it is to connecting researchers with government, industry, and community representatives throughout the entire research process – from development to implementation to evaluation. Indeed, developing and growing our perspectives on, and approaches to, research and innovation cannot be done in isolation. Rather, creating and pursuing strong partnerships across disciplines and sectors can help us all to pursue better approaches to research, policy, and practice that are aligned with the needs, goals, and priorities of all those involved.

And then we made a podcast… Adventures in integrative knowledge mobilization

Written by Lindsay Day, MSc Candidate It was with great excitement that we launched the “Water Dialogues” podcast last week at www.WaterDialogues.ca.

Nearly a year in the making, the collaborative podcast is based on a Canadian Water Network-funded project, and examines the need for, and our struggle towards, using Indigenous and Western knowledge systems together to address the water issues we face in Canada today.

Audio-recordings were taken during a Water Gathering event that brought together First Nations, Inuit, Metis and non-Indigenous water experts, researchers, and knowledge holders from across Canada.

This Water Gathering was the second of two that were held as part of the 18-month research project. Held at the Wabano Aboriginal Health Centre in Ottawa (traditional Algonquin territory), the format was a series of sharing circles, where every person has a turn to speak and all voices are valued equally.

Using a narrative, audio-documentary format, the podcast weaves together the voices, stories and experiences of those that attended the Gathering in order to explore the key issues and findings from the project.

The result is something powerful, moving, and definitely worth a listen.

Follow the conversation on Twitter: #H2Odialogues

https://twitter.com/indianandcowboy/status/733142489872244736

https://twitter.com/copeh_canada/status/732973197155536897

https://twitter.com/akolonich/status/733379366915211264

https://twitter.com/stephmasina/status/734493463635460096

https://twitter.com/jamiesno/status/732991086109450240

A huge thank you to all the podcast team members: Dr. Sherilee Harper, Dr. Ashlee Cunsolo, Dr. Heather Castleden, Dr. Debbie Martin, Catherine Hart, Tim Anaviapik-Soucie, George Russell Jr., Clifford Paul. And of course, to all the amazing people who shared their words, stories, wisdom, ideas and knowledge at the Water Gathering and in the podcast.

Listen and learn more at www.WaterDialogues.ca.

EcoHealth at the Pegasus Conference!

The 2016 Pegasus Conference was, by all accounts, an interesting, thought provoking, and inspiring conference. With themes of peace, global health, and sustainable solutions, conference delegates shared their expertise in research, education, field experiences, advocacy and policy to reduce disparities, inequities and social injustices. Speakers included leading voices in environmental change, justice, and health, including Naomi Klein, Anne Andermann, Janet Smylie, Peter Donnelly, among other accomplished leaders. It was certainly an honour and privilege for our research group to be a part of a plenary session on Environmental Stewardship & Global Change; Dr. Sherilee Harper joined Dr. Jean Zigby (President, Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment), Dr. Peter Victor (professor, York University), and the impressive and fierce Linda Wood-Solomon to explore the topic via short presentations and a discussion facilitated by the very talented Petra Hroch.

To follow the Twitter conversation, follow @PegasusConf and #PEGASUS16. Here are some highlights from the Environmental Stewardship & Global Change panel:

https://twitter.com/jaitrasathy/status/731854118785044480

https://twitter.com/TwonClarke/status/731847774916972544

https://twitter.com/twpiggott/status/731844463828606976

https://twitter.com/twpiggott/status/731843363801042947

Congrats to Rebecca Wolff on her Publication in National Geographic's Explorers Journal!

Congratulations to Rebecca Wolff for her recent publication in National Geographic's Explorers Journal!

To read her article, entitled "Indigenous Amazonians Reeling From Oil Spills in the Jungle," click here!

A Tale of Two Conferences

Written by Alexandra Sawatzky, PhD Student During the week of April 25, I had the privilege of attending and presenting at two conferences: the Sparking Population Health Solutions International Summit in Ottawa, and the Transforming Health Care in Remote Communities conference in Edmonton. These incredible experiences, although separated by approximately 3500 kilometers, did an outstanding job of bringing people and their ideas together. I had Great Expectations for these conferences, which ended up being exceeded in every way possible.

Tale #1: Sparking Solutions

The purpose of this Summit was to unpack and examine the wealth of knowledge we currently have about population health problems. To do this, individuals were brought together from across various sectors to challenge, catalyze, ignite, debate, stimulate, and accelerate ideas surrounding population-oriented solutions for a healthier future.

The purpose of this Summit was to unpack and examine the wealth of knowledge we currently have about population health problems. To do this, individuals were brought together from across various sectors to challenge, catalyze, ignite, debate, stimulate, and accelerate ideas surrounding population-oriented solutions for a healthier future.

Soon after my arrival, I quickly discovered I was one of only a handful of students in attendance. Predominantly, the crowd consisted of government representatives, policy-makers, and researchers – all important decision-makers, and all of whom had substantially more experience than me. Needless to say, I felt a little intimidated.

At the same time, I felt inspired to use this conference as an opportunity to soak up as much information from as many people as possible, as well as continue to develop some of my own perspectives on some of the issues being discussed. I slowly realized that despite my lack of experience, people genuinely wanted to hear my perspectives as much as I wanted to hear theirs.

During the first plenary session, the presenters asked simple, yet provocative questions that encouraged all of us to start to challenge our previously-held perspectives on various population health problems and associated solutions. Questions such as: why the sudden need to refocus and “spark” new solutions? Why do we feel that there are currently no solutions? Whose solutions matter? These provocations proved to be recurring themes for the rest of the conference.

As discussions surrounding these themes evolved, I found myself beginning to think more critically about current approaches to population health research, policy, and practice. As Dr. Mark Petticrew1 expressed in his plenary session, those working in the realm of population health often find themselves to be “prisoners of the proximate,” concerned mainly with the outer layers of population health problems. In reality, these problems possess deep, complex roots, meaning we need to dig a little deeper if we want to develop effective and sustainable solutions. Dr. Petticrew went on to suggest that the entire population health research system needs to be redesigned so that our focus is upstream, or at the root of the health problems that populations are facing.

A major barrier to this whole-system overhaul is the fact that most people (researchers included) are constrained by the limitations of their own knowledge and biases, and have the tendency to be over-reliant on a single way of knowing about the world (their own). In her plenary talk, Dr. Jennie Popay2 said this over-reliance on single perspectives needs to change – we need to make more of an effort to include multiple knowledge sources in the work we do. Indeed, the only way to fully understand the context and complexities of population health issues is by drawing upon the practical knowledge that is intrinsic to the specific populations we work with. We have an obligation to learn from the people who experience the world in different ways than we do.

It’s important to remember that learning about (and from) different perspectives is not about finding out who is “right” or “wrong,” it’s about engaging in dialogue and understanding where the other person’s knowledge about a certain issue comes from, and subsequently respecting that person as a knowledge-holder. Furthermore, new knowledge needs to be co-produced and merged throughout the entire research process, and this sort of “blended knowledge” holds the potential for greater positive impacts and lasting solutions.

Dr. Penny Hawe3 took this idea one step forward and suggested that researchers should not actually be taking credit for the solutions they help to develop. After all, if researchers follow true community-based, participatory approaches, the credit should ultimately go to the community – those groups of people who develop and implement solutions to problems they themselves identify. Essentially, the idea is that researchers should not take ownership, or demand thanks, for the outcomes of collaborative, community-driven efforts. Dr. Hawe emphasized that there is a great deal of humility in thinking about ways to harness the power of a community in this type of research. In order to fully capture and utilize this power, research needs to move beyond the walls of academic institutions and into communities. To breach these walls, communities must not only be in control of the research, but must also be given the credit they deserve.

In the final plenary session, Dr. Hawe singled out my team’s research project as an example of effective and meaningful community-driven population health research. It took me a moment to fully clue in that she was talking about our project, and once I did I felt a wave of gratitude wash over me. To be working with a team that places the needs, goals, and priorities of communities at the heart of everything they do is an immense privilege, and is helping to shape who I am in my research and beyond.

After all this discussion about sparking population health solutions, it’s important to ask what “solutions” even mean in the context of research, policy, and practice. The language surrounding the concept of “solutions” implies that there is an end-goal, or a static outcome that is the result of problem-solving efforts. However, solutions should be viewed as generative processes that evolve alongside population dynamics, and need to be maintained in order to stay relevant and effective.

Continuing to engage in dialogue about problems and solutions in population health is crucial. Individual researchers cannot possibly “solve” complex solutions on their own. Similarly, governments and policy-makers cannot make decisions on their own. Coming together and learning from one another at conferences such as such as this one can serve as an opportunity to challenge each other to spark creative and innovative solutions to population health problems, as well as hold each other accountable to continue feeding the flames.

Tale #2: Transforming Health Care

After a couple days of sparking population health solutions in Ottawa, I hopped on a plane to Edmonton to attend conference number two – “Transforming Health Care in Remote Communities.” In addition to switching time zones, I was switching gears slightly to focus specifically on health and health-care challenges as they pertained to remote communities in Canada, Nordic countries, Greenland, Alaska, Russia, and Australia.

An opening prayer and song from Elder Be’sha Blondin4 set the stage for what would be a humbling, emotional, and inspiring couple of days. This truly was a beautiful moment – to be standing in a room filled with individuals from around the world, with the steady beat of Be’sha’s drum making us feel as though all our hearts were beating as one. Later that day, Be’sha gave an incredibly profound and powerful talk about connecting and reconnecting the land and culture in order to be well. She emphasized that the land provides all that is needed for good health – freedom, and healing. When people are out on the land, they are their best selves. It is therefore important to work on, and help each other achieve this sense of wellness that is intrinsically woven into each and every one of our souls. Be’sha ended her talk by stating that working together in a holistic way will not only improve health and health care in rural and remote communities, it will heal the world.

This theme of holistic approaches to health care was among several other themes that had been brought up at the Sparking Solutions Summit in Ottawa, and that resonated throughout many of the presentations at this conference in Edmonton as well. I found this congruency to be fascinating, especially considering that at this conference, delegates included researchers, clinicians, managers, policy makers, service providers and representatives of industry, non-governmental organizations and indigenous communities from vastly different parts of the world. I think this just goes to show that despite the diversity of geographic locales, we still share many common stories and values when we talk about health and health care within and between populations – remote or otherwise.

When discussing remote communities, it’s important to think the weight of the term “remote,” and what that community is “remote” in relation to. Places that we consider to be remote are in fact places that someone else considers to be home. Moreover, in the context of population health, remoteness is often constructed as problematic, as pathology – it is a barrier that needs to be worked around in order to improve health and health care systems, it is a barrier to improvement. There is therefore a need to design new systems. Instead of trying to adjust current approaches to health care so that they work in remote communities, these approaches need to be redesigned so that the remoteness of a community is a defining characteristic, or core component, of an entirely new system; remoteness should be framed as an opportunity, not a barrier.

Dr. Graeme Maguire5, in his keynote address, said that designing health care policies for “everyone” – using a one-size-fits-all approach – is not effective. Essentially, “remote” should not be used a pejorative term. Just because a community is remote does not mean it is disadvantaged. Remote places are simply just another type of cultural landscape where the environment, community and cultural issues intersect in unique and interconnected ways. Understanding that we need to move beyond anecdote-driven policy that often perpetuates disadvantage, and seek to focus our attention on those who are often forgotten in health care systems.

Transforming health care involves transforming knowledge relationships between the people, places, policies, costs, data, links, and tools that both determine and support the health of communities. Reverse innovation, an idea brought up by Dr. Maguire, involves the multidirectional knowledge translation and exchange within and across groups. Equity-focused health indicators are needed to inform and evaluate inclusive health care policy and practice. Focusing on equity necessarily means focusing on the upstream determinants of health, as transformational change cannot be driven from downstream. There are many barriers to initiating these types of changes, particularly due to competing priorities of different partners, and fragmented systems that make it difficult to work to align these priorities. Furthermore, whether we’re working upstream or downstream of population health problems, the “stream” itself is moving fast. Thus, we need cohesive, collaborative action. We need to foster healthy, supportive partnerships in order to not only navigate through this fast-moving stream of challenges, but to start to redirect it towards more meaningful and lasting solutions.

What happens when partnerships are made between researchers and Indigenous communities, and what is needed to help make these partnerships work? In a word, trust. Trust is fragile. It is hard to gain and easy to lose. It is built upon a foundation of shared values, honesty, patience, and intergenerational humility. Trust is very intimate and needs to be earned.

A panel presentation by the CANHelp Working Group – a group of researchers from the Univerity of Alberta and community partners from the Yukon as well as the NWT – expanded on this essential need for trust between all stakeholders involved in research projects. The panel emphasized that researchers need to balance academic needs for discourse and outcomes with community needs for meeting the goals and priorities they themselves initially set out. Moreover, as partners in research efforts, communities need to hold researchers accountable for their actions. Both the intentions and end-results of research are equally important, and researchers must continue to build and maintain trust even after a project is finished.

Researchers must approach their relationships with communities from a place of humility, with a willingness to learn and participate. I believe that actively working to achieve this balance is a way of showing a community that they can indeed trust you to be a good researcher, and a good person. The overarching theme of this last panel discussion, and of the conference in general, was that it’s not enough to participate in community-based research. Researchers need to participate in community.

Footnotes:

- Mark Petticrew is a professor of Public Health Evaluation in the Faculty of Public Health and Policy at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK.

- Jennie Popay is a professor of Sociology and Public Health at Lancaster University, UK.

- Penny Hawe is a professor and co-lead investigator of the NHMRC Australian Prevention Partnership Centre.

- Be’sha Blondin is a Sahtu Dene Elder from Tulita, Northwest Territories with forty years of experience in Indigenous traditional healing and living in harmony and balance.

- Graeme Maguire is a professor and head of clinical research at Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne and Alice Springs, Australia.

IHACC end-of-project knowledge sharing workshop in Iqaluit, Nunavut on April 25th

Team members from the IHACC project Arctic team were in Iqaluit on Monday April 25th to host a workshop with participating community members and partners at the Nunavut Research Institute to share knowledge and insights gained throughout the 5 years of the project. Team members present included Dr. James Ford, Dr. Victoria Edge, Dr. Sherilee Harper, Dr. Ashlee Cunsolo Willox, Ms. Anna Bunce, Ms. Mya Sherman and Ms. Jolène Labbé. Workshop participants were given a wealth of materials produced from the project, including copies of scientific papers, reports, results booklets, posters, and presentations. We look forward to future collaborations in the community as IHACC moves to an end, and follow-up projects begin to take shape!

OVC Graduate Student Recognition Award Winner!

New Publication!

Congratulations to Ellen McDonald on the first publication from her MSc thesis! Citation: McDonald, E.M., Papadopoulos, A., Edge, V.L., Ford, J., IHACC Research Team, Harper, S.L. (2016). What do we know about health-related knowledge translation in the Circumpolar North? Results from a scoping review. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 75(31223), 1-17. Click here to access the article (open access).

Title: What do we know about health-related knowledge translation in the Circumpolar North? Results from a scoping review

Abstract:

Background. Health research knowledge translation (KT) is important to improve population health outcomes. Considering social, geographical and cultural contexts, KT in Inuit communities often requires different methods than those commonly used in non-Inuit populations.

Objectives. To examine the extent, range and nature of literature about health-related KT in Inuit communities.

Design. A scoping review was conducted. A search string was used to search 2 English aggregator databases, ProQuest and EBSCOhost, on 12 March 2015. Study selection was conducted by 2 independent reviewers using inclusion and exclusion criteria. To be included, studies had to explicitly state that KT approaches were used to share human health research results in Inuit communities in the Circumpolar North. Articles that evaluated or assessed KT approaches were thematically analysed to identify and characterize elements that contributed to KT success or challenges.

Results. From 680 unique records identified in the initial search, 39 met the inclusion criteria and were retained for analysis. Of these 39 articles, 17 evaluated the KT approach used; thematic analysis identified 3 themes within these 17 articles: the value of community stakeholders as active members in the research process; the importance of local context in tailoring KT strategies and messaging; and the challenges with varying and contradictory health messaging in KT. A crosscutting gap in the literature, however, included a lack of critical assessment of community involvement in research. The review also identified a gap in assessments of KT in the literature. Research primarily focused on whether KT methods reflected the local culture and needs of the community. Assessments rarely focused on whether KT had successfully elicited its intended action.

Conclusions. This review synthesized a small but burgeoning area of research. Community engagement was important for successful KT; however, more discussion and discourse on the tensions, challenges and opportunities for improvement are necessary.

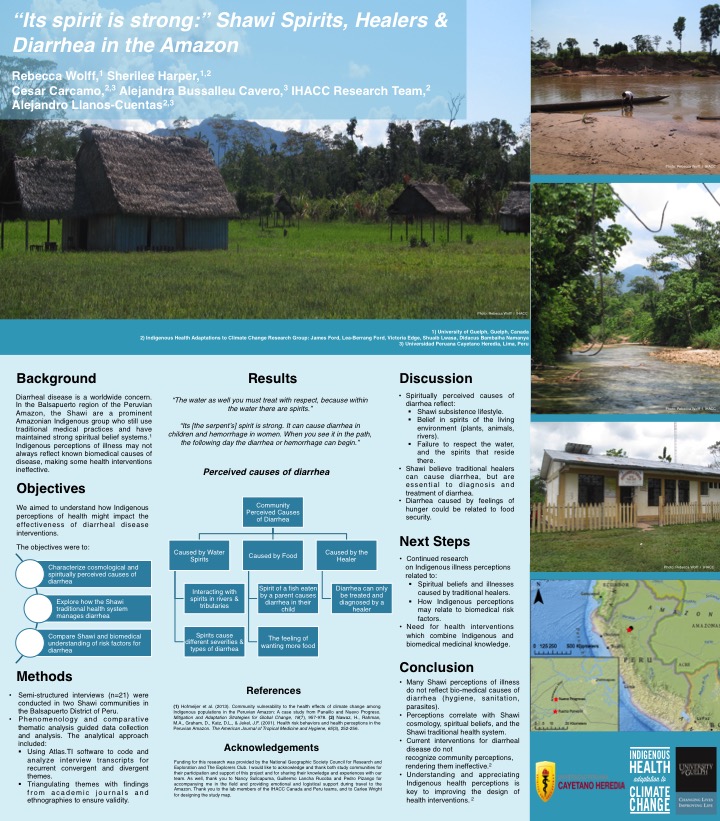

Rebecca Wolff Presents at 2016 Consortium of Universities for Global Health!

Congratulations to Rebecca Wolff for sharing her research results at the 2016 Consortium of Universities for Global Health in San Francisco! Poster citation: Wolff, R., Harper, S.L., Carcamo, C., Bussalleu Cavero, A., IHACC Research Team, and Llanos-Cuentas, A. (April 2016). “Its spirit is strong:” Shawi Spirits, Healers & Diarrhea in the Peruvian Amazon. Consortium of Universities for Global Health 2016 Conference, San Francisco, USA.

InukBook covered by Canadian Geographic

The InukBook program was recently highlighted by Canadian Geographic in an interview with Dr. Ashlee Cunsolo. "Thawing permafrost and other changes in weather and precipitation patterns are having a number of adverse effects on Inuit culture, not the least of which being climate change-related health impacts like increased risk of injury due to unstable ice. Today, “monitoring” is the foremost recommended health/climate strategy. Many monitoring structures in place in the North, however, aren’t organized to reflect the values and preferences of Indigenous people. Cue the InukSUK program (with SUK standing for strength, understanding and knowledge, principles that underpin Inuit notions of health and wellbeing)...." Click here to read the article.

Congrats to Nia King on her National 3M Award!

Congrats to Lab Member Nia King for her National 3M Award, recognizing her work with Dr. Cate Dewey in Kenya.

For more information, click here.

PhotoVoices of the Harper Lab: Reflections on the Health-Place Nexus

Written by Alexandra Sawatzky, PhD student Over the course of this semester, members of our lab group have been taking turns facilitating our bi-weekly lab meetings. Jacquie and I were in charge of last week’s meeting, and given that the end of the semester is fast approaching, we thought we would take the opportunity to lead an activity that might help to alleviate some of the end-of-semester stress while also encouraging some self-reflection.

A lot can happen in one semester. The months often fly by without leaving us much time to reflect on what we’ve learned, or how much we’ve grown. It’s easy to feel a little lost and overwhelmed amidst all of the coursework, teaching, travel, and extracurriculars.

“Stress management” techniques such as getting enough sleep, meditation, and exercising can be helpful, but they don’t necessarily help you tackle the root of the problem. Increasing attention has been paid to the benefits of self-reflection, specifically in terms of articulating those “…core values that help us weather the storms and devastations that inevitably rock our lives and careers…followed by action steps to implement those values in interpersonal settings” (Brendel, 2015).

One way to help identify those core values is to reflect on the places that play a role in shaping who you are and how you perceive the world. For example, Basso (1996), writing within the context of a Western Apache tribe, talks about stepping back from everyday experiences and incorporating an awareness of sense of place into self-reflection:

“places possess a marked capacity for triggering acts of self-reflection, inspiring thoughts about who one presently is, or memories of who one used to be, or musings on who one might become” (p. 55).

As such, reflecting on the way certain places make us feel can help us to assess and deal with our current situations, as well as work towards improving our future. Identifying the places where you feel most connected to the world – and to yourself, for that matter – and making conscious efforts to continue connecting with those places can help you to develop your own personal recipe for resilience during stressful times.

Recognizing that we certainly couldn’t accomplish all this in an hour, Jacquie and I came up with a more focused self-reflection exercise, using a photovoice framework. Following an approach laid out by Mulder and Dull (2014) involving the use of photovoice to encourage self-reflection and self-awareness among Master’s of Social Work students, we sought to turn the focus of this method inward, towards ourselves as graduate students.

We asked members of our lab group to share photos of places that were important to them. We encouraged each person to describe why each place was important, how it came to be important, as well as how that place made them feel.

Essentially, these places were important because they told stories. As everyone shared their photos and associated stories, several cross-cutting themes became clear.

- We use these places as a means to describe our past experiences as well as our future goals. Often, we choose our favourite places based on where we feel most ourselves, or where we feel the best parts of ourselves are brought out. These are places where we get much of our thinking done. From reflecting on past experiences, to envisioning our future, these places, as one individual stated, are “…where everything comes together – [they] put everything in perspective, and help with making decisions.”

- Familiar places instill in us a sense of consistency. We draw a lot of meaning from places we visit often. Even though we may change substantially between the times where we get to visit these places, we can usually count on the environment itself to stay relatively the same. One person even mentioned that, “it’s been many years since I’ve been there, yet I still know it so well.”

- Discovering and exploring new places was associated with turning points, or life-changing moments that led to growth, change, and independence. As such, new places can become just as important as places we’ve known our whole lives. It’s a strange but wonderful feeling when you are able to instantly adapt to/fall in love with a new place.

- With everything we have going on in our lives, sometimes finding a healthy balance seems impossible. As such, we tend to gravitate towards certain places as a sort of escape from reality. Interestingly, the places each of us went to “get away from it all” were just as distinct and diverse as the things we are trying to get away from. However, these places all served a common purpose: for us to reset, rejuvenate, and renew ourselves.

- These places are special, and the people we’re with make them that much more special. Although the relationship we have with these places are highly personal, friends and family have a strong influence on the depth of our relationship to a certain place. Indeed, our relationships with other people can be an integral part of our relationships with places. For example, when speaking about a place she visited with her family, one individual said, “I am really influenced by the people around me. I love being around jovial groups – people who are as excited as I am to be there.”

- Certain spots make you feel as though you are in exactly the right place, at exactly the right time. It takes a special place to make us feel fully present and truly peaceful.

Overall, this activity encouraged us to discuss some of the places we hold close to our hearts, and explore how these places helped lead to the development of our values and perceptions. Our discussions combined introspection, creativity, and the integration of multiple perspectives into a comprehensive self-reflection process.

Identifying and understanding those places where we feel most connected can also help us on our journey toward figuring out who we are and what we value. These places serve to remind us where we come from, as well as reveal how much we’ve grown. New places can help us look at old places in different ways, and perhaps understand more deeply what these mean to us.

We need these places for so many reasons – for all aspects of wellbeing. However, these places don’t necessarily need us in this same way. It’s easy to forget that when we’re not in that place, the place is still there. Indeed, our favourite places will be there long after we’re gone. These places give us so much – a sense of connectedness, feelings of peace and tranquility – we don’t think about what or how we can give back. Or if we can give back at all. Maybe the best thing we can give back is simply our pure and utmost gratitude.

References:

Basso, K. H. (1996). “Wisdom Sits in Places: Notes on a Western Apache Landscape.” In Feld, Steven, and Basso (eds.) Senses of Place. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 53-90.

Brendel, D. (2015). “Manage Stress by Knowing What You Value.” Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2015/09/manage-stress-by-knowing-what-you-value

Mulder, C., and Dull, A. (2014). Facilitating self-reflection: the integration of photovoice in graduate social work education. Social Work Education, 33(8):1017-1036.

MSc Graduate Sarah Syer Transitions from Researching Paediatric Malnutrition to Childhood Cerebral Palsy!

After graduating from the EcoHealth Lab where she studied childhood malnutrition, Sarah Syer is continuing her health research career as a Research Assistant at ErinoakKids Centre for Treatment and Development (Mississauga). The research project she is working on is funded by the Ontario Brain Institute (OBI) and is called CP-NET (Childhood Cerebral Palsy Integrated Neuroscience Discovery Network), which aims to improve the understanding of cerebral palsy and accelerate the development of new treatments. She is working closely with a developmental paediatrician, who is the principle investigator at the ErinoakKids site.

Interested in learning more about the organization that Sarah is now working with? Click below to learn more about OBI's plan and goals for the project:

After graduating from the EcoHealth Lab where she studied childhood malnutrition, Sarah Syer is continuing her health research career as a Research Assistant at ErinoakKids Centre for Treatment and Development (Mississauga). The research project she is working on is funded by the Ontario Brain Institute (OBI) and is called CP-NET (Childhood Cerebral Palsy Integrated Neuroscience Discovery Network), which aims to improve the understanding of cerebral palsy and accelerate the development of new treatments. She is working closely with a developmental paediatrician, who is the principle investigator at the ErinoakKids site.

Interested in learning more about the organization that Sarah is now working with? Click below to learn more about OBI's plan and goals for the project:

http://www.braininstitute.ca/cpnet/CP-intro.html

Farewell and congratulations Sarah!

Best of luck with all of your future endeavours and adventures!

Climate Change IFS3 Meeting with Ugandan Colleagues

Last week we convened in Montreal for productive, insightful, and fun meetings with colleagues from Uganda, South Africa, and McGill to begin planning for the Climate Change and Indigenous Food Systems, Indigenous Food Security, and Indigenous Food Safety (Climate Change IFS3) project.

Alexandra Sawatzky Reflects on her Work in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut

Written by Alexandra Sawatzky (PhD Student) Almost immediately upon returning from my trip to Rigolet in February, I was faced with the unavoidable, arguably unanswerable, question: so, how was it?

Even after having had time to reflect and process everything, I still struggle with answering this question. There is no way I can articulate exactly how I feel about Rigolet, about the incredible people I get to work with here, and about the project that I am lucky enough to be a part of. I think this struggle with putting my feelings into words is largely due to the fact that the project, the people, and the place are all intertwined, and they all became a part of my life so easily and so quickly that my words have trouble catching up to my emotions.

Before my first trip to Rigolet this past October, I was incredibly nervous. I was so intimidated at the prospect of being involved in such a large, interdisciplinary project. I didn't exactly know where I would fit, let alone what the community would think of me. But as soon as I stepped off that first Air Labrador flight, all my fears disappeared and I knew I would never be the same.

Fast forward a few months, and before I knew it, I was back on a plane headed North with Dan, Oliver, and Ashlee. It was an amazing feeling, and an enormous privilege, to have the opportunity to return to Rigolet. Again, I was nervous, but this time my pre-trip jitters had more to do with being overwhelmingly excited to continue moving this project forward, to reconnect with people in the community, and to experience winter in all its Northern glory.

For a bit of background, our research involves the participatory development of a surveillance system, led by the community of Rigolet, to to track and respond to changes in the environment and resulting impacts on health and wellbeing. The basis of the approach we're taking to build this project is to listen, learn, understand, and then respond to what the community needs and wants. To start this process, back In October we asked members of the community five main questions in a series of interviews and focus groups: (1) what are some important issues with regards to the environment and health; (2) what sorts of changes in the environment and resulting health impacts are you noticing in your community; (3) of these changes, what do you think is important to monitor/track; (4) how are you already keeping track of these changes; and (5) what sorts of tools/technologies (if any) are you using to do so?

As I was preparing to return in February, I thought critically about what we had learned from the community thus far, and how we might build off these initial discussions surrounding important environment-and health-related issues. However, in order to build from these discussions and move forward with the project in an appropriate way, I first needed to develop a deeper understanding of the reasons why these issues were important, who they were important to, and how they were prioritized. In short, I needed to ask some new questions.

I sat down with many of the same individuals who I had met with in October to present the preliminary findings and ask for their feedback. Then, I asked: (1) why are these issues important to you; (2) how would you prioritize these issues; (3) what are some ideas you have that could help make this program engaging and easy for people to use?

With each person or group I spoke with, my mind was blown over and over again by the depth and breadth of wisdom that is held in Rigolet. One of the key points brought up in this round of brainstorming sessions was that we need to work together to create a program that wouldn't necessarily feel like a "program" - we need to create something that can be seamlessly incorporated into day-to-day life. Conversations like these made me realize over and over again what an honour it is to be working with and learning from this community. As always, the ways in which people described their connections to and relationships with the land absolutely blew me away. Although I will never even begin to know the true depth of the love that’s shared here between the land and its people, I am so grateful to be taking part in this learning journey.

During our trip, we also had the opportunity to engage in some hands-on, experiential learning on the land. Within a few hours of arriving in Rigolet, we took off with Sandi and Karl - our gracious hosts and dear friends - to spend the weekend at their cabin on English River – about a 2.5-hour skidoo ride outside of the community (mind you, this same trip typically takes Sandi and Karl about 1.5 hours). From the moment we left, we knew this would be the adventure of a lifetime. We left Rigolet in the late afternoon, and as we were making our way across Lake Melville we witnessed the most stunning sunset any of us have ever seen. The only description that somewhat captures this experience is that it felt like gliding above the surface of the clouds; hard to tell where the ice ended and the sky began. Unfortunately, I don’t have any photos of this magical experience because it was way too cold to stop and pull out my camera. Yet, there is something to be said for just living in the moment and absorbing the surroundings without viewing them through a lens. Moreover, there is no way a photo could have captured that kind of beauty anyway (at least, no photo that I could take).

Our weekend at the cabin was filled with fun, adventures, and delicious food (everything tastes better when cooked on a wood stove). We had a massively successful ice fishing escapade, and Oliver and I even skinned our first rabbits under Sandi’s patient instruction and watchful eye. Sandi and Karl, I don’t think we can thank you enough for keeping us full, safe, warm, and smiling.

This experience also gave us many important insights that will be absolutely crucial to incorporate into our project as we learn to better understand how technological tools can help people keep track of various environmental observations and changes while they are on the land. For example, our phones and cameras would freeze at times, so using them outside in certain conditions was not feasible and is something we need to account for in developing the project. There was definitely something to be said about learning how to navigate through these unanticipated challenges firsthand.

Upon reflection, I am realizing that this project, these people, and this place all share the same part of my heart - a part of my heart that I most certainly didn’t realize was missing until I found it. I feel so fortunate to be working with a team of community partners and researchers that is so incredibly supportive of each other. We hold the same basic values, share a deep and indescribable love of the North, and we take our research as seriously as we do our long underwear and scavenger hunts. Through these experiences, I’m finding that in order to do your best work and be your best self, it helps to be surrounded by people who bring out the best parts of you.

In terms of the place, its immense beauty never ceases to amaze me. There are really no words, only feelings. The colours are brighter, the food is tastier, the air is fresher, and life feels more authentic. It’s a place where I can let my guard down, open myself to change, and challenge myself to grow. But no matter what I say about it or how I try to describe it, there is so much more that I can't even begin to describe. That which no words can capture. I truly feel as though I left a part of my heart there. This is something I struggle with articulating because I know that no matter how much I learn about/love this place, I will always be an outsider, a stranger to the land. I will never know the love that these people have for their homeland, and that which the land has for them. So thank you, Rigolet, for welcoming us Southerners with open arms and allowing us to share in your incredible beauty and wonder. As I'm slowly running out of words to capture how I feel about working, learning, loving, and growing in this place, I'll call upon the help of Richard Wagamese, an Ojibway author:

“To be struck by the magnificence of nature is to be returned again, in those all too brief moments, to the innocence that we were born in. Awe. Wonder. Humility. We draw it into use and are altered forever by the unquestionable presence of the Creator. All things ringing true together. Carrying that deep sense of communion back into our work-day life, everyone we meet becomes the direct beneficiary of our having taken the time for connection, prayer, and gratitude. This is what we are here for - to remind each other of where the truth lies and the power of simple ceremony.”

Community Consultations on the PAWS Project

Written by Anna Bunce Consultations for the People, Animals, Water, and Sustenance (PAWS) project continued last week in Iqaluit as Dr. Jan Sargeant and myself were in town meeting with community stakeholders to determine the priorities for the quantitative portion of the work. As a goal of this work is to provide useful, relevant information to stakeholders we have been consulting with a variety of stakeholders in Iqaluit since the idea for this project first came to be. Last week was just another part of our consultation, but an exciting one. Dr. Sargeant and I presented a series of potential scenarios to stakeholders and asked them to help prioritize which pathogens we should test for and what sources we should test. With so many options it immediately became clear that we would need something to break down all the options, and so a “menu” of sorts was created, laying out the options of what pathogens we could look at and which sources we could test for these various pathogens. The outcome was a very productive and informative meeting, where we were able to brainstorm ideas and talk about the pros and cons of each possible scenario. After having a “dotmocracy” session, where stakeholders ranked their preferences using a series of dots, we have a clearer idea of priority areas and are looking forward to following up with more meetings in March. A big thank you again to all the stakeholders who took time out of their busy day to meet with us!

Anna Bunce is the project manager for the PAWS Project. Having recently completed her Masters at McGill University looking at how Inuit women are experiencing and adapting to climate change in Iqaluit, she is excited to continue working in Iqaluit, Nunavut with the PAWS project.

Congratulations to Sarah Syer for Completing her MSc!

Congratulations to Sarah Syer for successfully defending her MSc research in January, and convocating with a MSc in Epidemiology this week! Photos below: Sarah at the UofG Grad Lounge receiving her customary Defense Mug; Sarah at UofG Convocation

Summer Undergraduate Research Assistant Needed!

We are hiring a summer undergraduate research assistant. Please see the job post and application instructions for details: https://www.uoguelph.ca/registrar/studentfinance/ura/jobs/ids/221